Housing and inequality

13.4% of households in England are considered to be in fuel poverty, with numbers forecasted to rise rapidly in 2022. Small measures like insulation and awareness-raising can make a significant difference to people’s incomes, especially those with low incomes or those vulnerable to the impacts of the cold.

- Improving the energy efficiency of individual properties has a significant impact on how much it costs to heat them.

- A disproportionate number of individuals who experience fuel poverty (37.6%) live in the private rented sector. Rented accommodation has the lowest energy efficiency rating of any housing sector.

- Over 158,000 low-income households in England live in properties rated below a band E EPC rating (F and G ratings). Fuel costs for the least efficient band G properties are almost three times higher than for band A-C properties.

- Increasing the energy efficiency of properties can therefore save a significant amount of money for the fuel poor whilst potentially also reducing carbon emissions. Given that the fuel poor spend a disproportionate amount of their income on energy consumption, energy efficiency measures can have a positive financial redistributive effect if those measures are funded appropriately.

Household energy efficiency improvement projects can create jobs, upskill the workforce and improve productivity.

They can also help to improve equality of opportunities for those from lower-income groups:

- Poor quality housing negatively affects the ability of young people to learn at school and study at home, leading to lower educational attainment, subsequently increasing their chance of unemployment and poverty.

- Nearly a quarter (23%) of parents say that they have gone without food to ensure that their children have enough to eat, with knock-on impacts on nutrition and household relationships.

Case Study: North East Derbyshire – Retrofitting homes at risk of fuel poverty

Upgrading hundreds of hard-to-treat council homes – lowering emissions and tackling fuel poverty.

Air quality inequalities

Decarbonising the transport sector will provide health benefits that save the NHS money while simultaneously addressing health inequalities. Air quality affects everyone, but the most socioeconomically disadvantaged almost always suffer the most from the health effects of pollution. Other groups disproportionately affected include older people, children, pregnant women, individuals with existing medical conditions, and communities in areas of higher pollution.

More Information

Learn more about health in Chapter 3 of this toolkit

There are strong geographical differences in the occurrence and concentration of pollutants. Analysis shows that these patterns, which vary by pollutant type, are related to measures of socioeconomic status, with pollution sources and higher concentrations of ambient pollution typically found in more socially disadvantaged areas.

Those most affected by air pollution in the UK are often those least responsible for producing it – it is vehicles passing through their neighbourhoods who are primarily responsible for causing the pollution rather than travel by those living within the area, as low-income communities are more likely to use public transport than private vehicles.

Pregnant women, communities with poorer air quality (e.g. those situated closer to main roads), children, older people (65 and older), and those with cardiovascular disease and/or respiratory disease.

Green space

Increasing the number of green and blue spaces (such as parks, trees, green roofs and ponds) within a community provides a multitude of benefits; as well as reducing flood risk, they can also reduce overheating and improve air quality. They have also been shown to have a positive impact on life expectancy and physical and mental wellbeing.

However, access to green space is not equal across England. The most deprived areas are less likely to be green areas, and people living there will therefore have less opportunity to gain the health benefits associated with green space compared with people living in the least deprived areas. Ethnic minorities are more than twice as likely to live in areas deprived of green space compared to white people.

Increasing the use of good quality green space for all social groups is likely to improve health outcomes and reduce health inequalities. It can also bring other benefits such as greater community cohesion and less social isolation.

Case Study: Hackney – Improving access to green spaces

Boosting access for less wealthy residents.

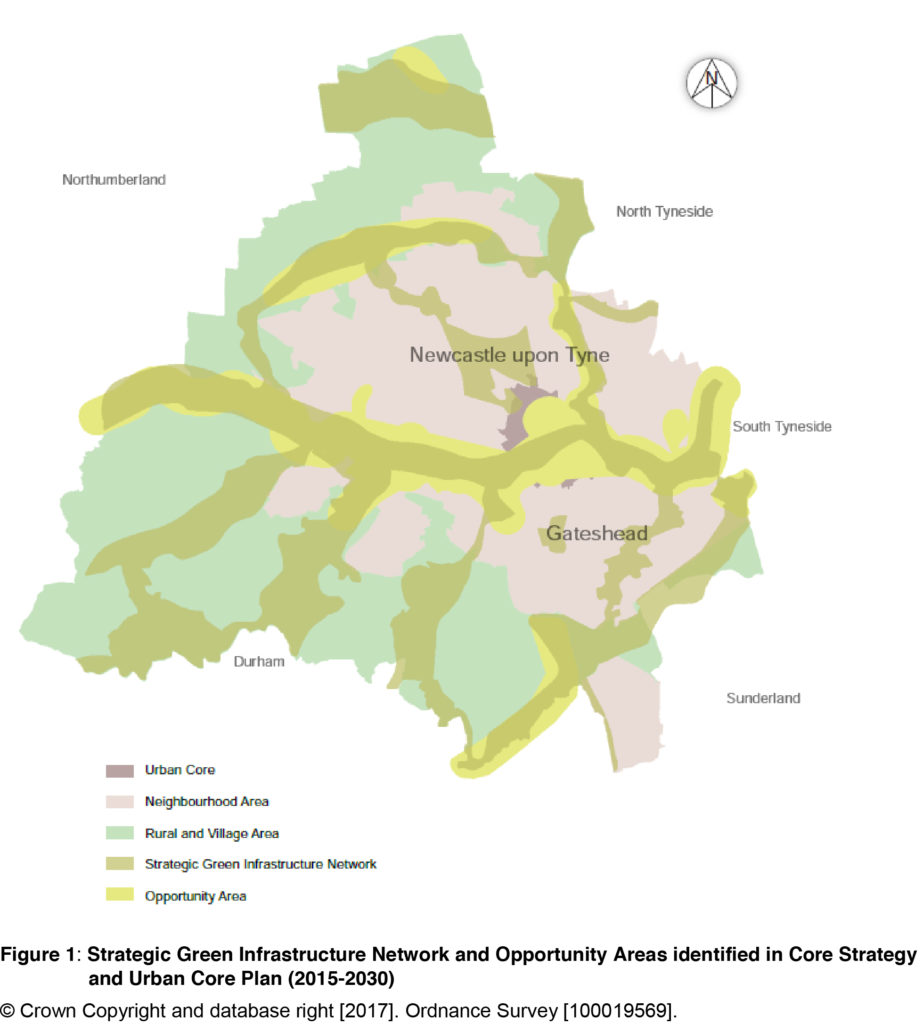

Example: Newcastle Green Infrastructure

Identifying co-benefits of green infrastructure including mental and physical health improvements.

Access to skills

As explained in Chapter 4, the transition to a low carbon economy risks leaving some workers behind. Councils can support labour market flexibility by providing training, or funding towards training, for individuals. There is also scope to work with and support initiatives, such as Repowering, which offer work placements and apprenticeships to local people.

More Information

Learn more about economy and skills in Chapter 4 of this toolkit

Climate change – a shared issue across all communities

Climate change is one of the few issues that has a global impact and provides an opportunity for getting all sections of the community involved in identifying solutions, increasing social cohesion.

More Information

Learn more about resilience and adaptation in Chapter 5 of this toolkit

Case Study: The Welcoming

Building green communities with refugees, migrants and asylum seekers.

Access to low carbon transport

Access to low carbon transport is patchy, with some groups having little option to make a low carbon choice. Cycling is a very lost cost low carbon transport option, but certain groups are much less likely to cycle than others. Working at a grassroots level to teach those with little or no cycling experience to ride confidently, especially in cities, can lay the foundations for a cycling culture.

Another low carbon transport option is car sharing. This can be particularly valuable for equity and social cohesion in areas where there is little option for public transport or in cases where people are no longer able to drive, e.g. through illness. In these circumstances, car sharing can offer a cost effective and relatively low carbon option to access workplaces and other facilities.

Example: Liftshare

Liftshare

2012 Ashden Award winner helping fill empty car seats on the roads while offering a friendlier, greener and cheaper way to travel.

Avoiding car dependency

Enabling people to travel by public transport, cycling or walking is critical for meeting our climate change targets and also for delivering the health benefits of cleaner air and increased physical activity. However, research has found that many new housing developments are still being designed in a way that forces inhabitants to be car dependent. This research found that the scramble to build new homes is producing houses next to bypasses and link roads which are too far out of town to walk or cycle, and which lack good local buses.

To help overcome this, the report recommends that land use and transport should be planned together, with local authorities working cross-boundary to analyse, design and fund public transport in tandem with the expansion of a whole area.

Example: Poundbury

A development designed around people rather than the cars, avoiding car dependency and creating a walkable neighbourhood.

Community energy and social benefits

A study by the National Trust found that community renewables schemes can deliver a range of social and economic benefits to local communities including increased autonomy, empowerment and resilience by providing a long-term income and local control over finances, often in areas where there are few options for generating wealth. Other benefits include opportunities for education, a strengthened sense of place and an increase in visitors to the area.

Community energy schemes can also offer training and apprenticeships to local people whilst also offering local people the chance to invest in energy generation with a very low minimum investment threshold. And several schemes use part of their profits to fund energy efficiency measures in fuel poor households. With smart metering technology, there is also the potential to offer local people discounted energy linked to local energy generation.

Example: Swaffham Prior Community Land Trust

Swaffham community heat scheme – bringing low-cost renewable heat to an off-gas community.

Previous Section:

6.1 Key facts and sources of information

Next Section:

6.3 Links to statutory duties